The Developing World: An overview

In the study of economic development, the term Developing World is often used as a convenient shorthand to group three broad regions: Africa, Asia, and Latin America. In this context, these labels function more as practical geographic and economic groupings rather than precise cultural or identity-based categories. Within each region, there is substantial diversity. Some countries are significantly more developed than others, and not all share the same historical, linguistic, or cultural backgrounds.

Latin America, for example, when defined in its broadest development context, can sometimes be taken to mean all of the Americas except the United States and Canada. This usage, while linguistically imprecise, stems from the fact that, outside these two highly developed nations, most countries in the hemisphere face similar economic challenges, are geographically proximate, and share historical experiences rooted in European colonization. In such a broad framing, the term becomes less about strict linguistic or cultural criteria and more about grouping together the less-developed nations of the Western Hemisphere for comparative and analytical purposes.

In development studies, there are no universally fixed definitions for regional or economic groupings. Analysts rely rather on widely used but flexible concepts. Understanding these concepts helps contextualize and interpret the literature on the developing world more effectively. The following sections will introduce and explain these terms and concepts.

Global North, Global South

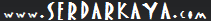

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) frames global discussions around a Global North–Global South divide, which broadly separates the more industrialized and affluent nations from the less-developed and developing ones. The Global North typically includes North America, Western Europe, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. These are states that have long-established industrial economies and high living standards. The Global South, by contrast, encompasses much of Africa, Asia, Latin America, and parts of the Middle East, where income levels, industrial capacity, and social development indicators tend to be lower.

The Global North & South according to UNCTAD

This framework too is not purely geographical. The North includes Southern Hemisphere countries like Australia, while the South can encompass Northern Hemisphere states such as India. It is primarily an economic and political classification that emerged during the Cold War, reflecting historical patterns of colonialism, resource extraction, and structural inequality. Today, the terminology is still widely used in global policy discussions, though it is recognized as a simplification of a far more complex reality.

Degrees of Underdevelopment

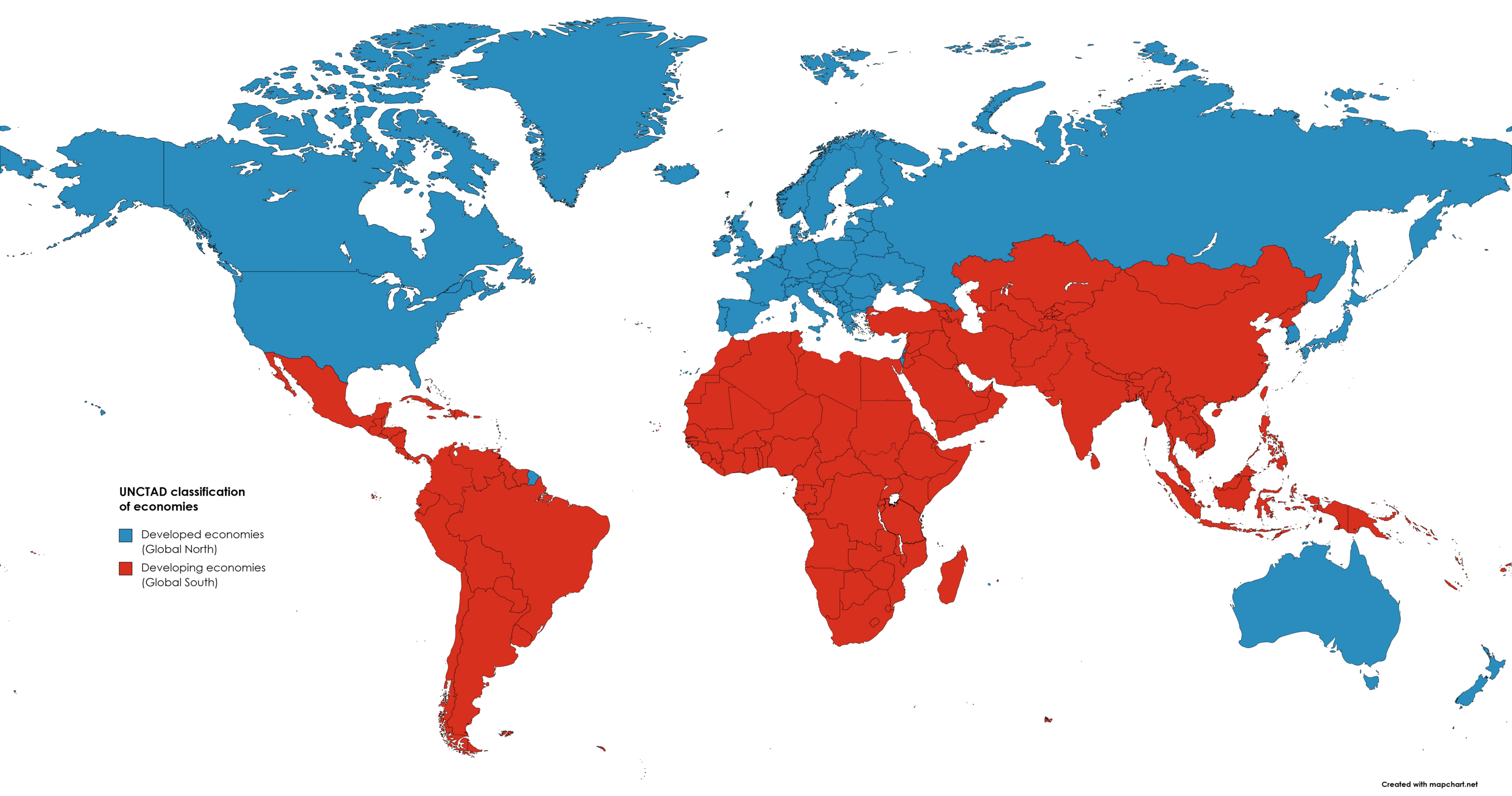

Within the Global South, there are varying levels of economic development. The United Nations designates a subset of the developing world as Least Developed Countries (LDCs) based on specific thresholds for income, human assets (such as education and health), and economic vulnerability (including exposure to shocks and environmental fragility). These countries often face structural barriers that make progress toward industrialization and poverty reduction particularly challenging.

Blue: Developed countries, according to the IMF

Orange: The Developing World, excluding the LDCs

Red: Least Developed Countries, according to the UN's Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC)

At the other end of the spectrum are emerging markets, a term used by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and other financial institutions to describe economies in transition toward higher levels of development and integration into the global economy. Emerging markets typically experience rapid growth, industrial diversification, and increasing foreign investment. The Four Asian Tigers are Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan, and they are often cited as emblematic success stories, having advanced from low- or middle-income status to high-income economies within a few decades.

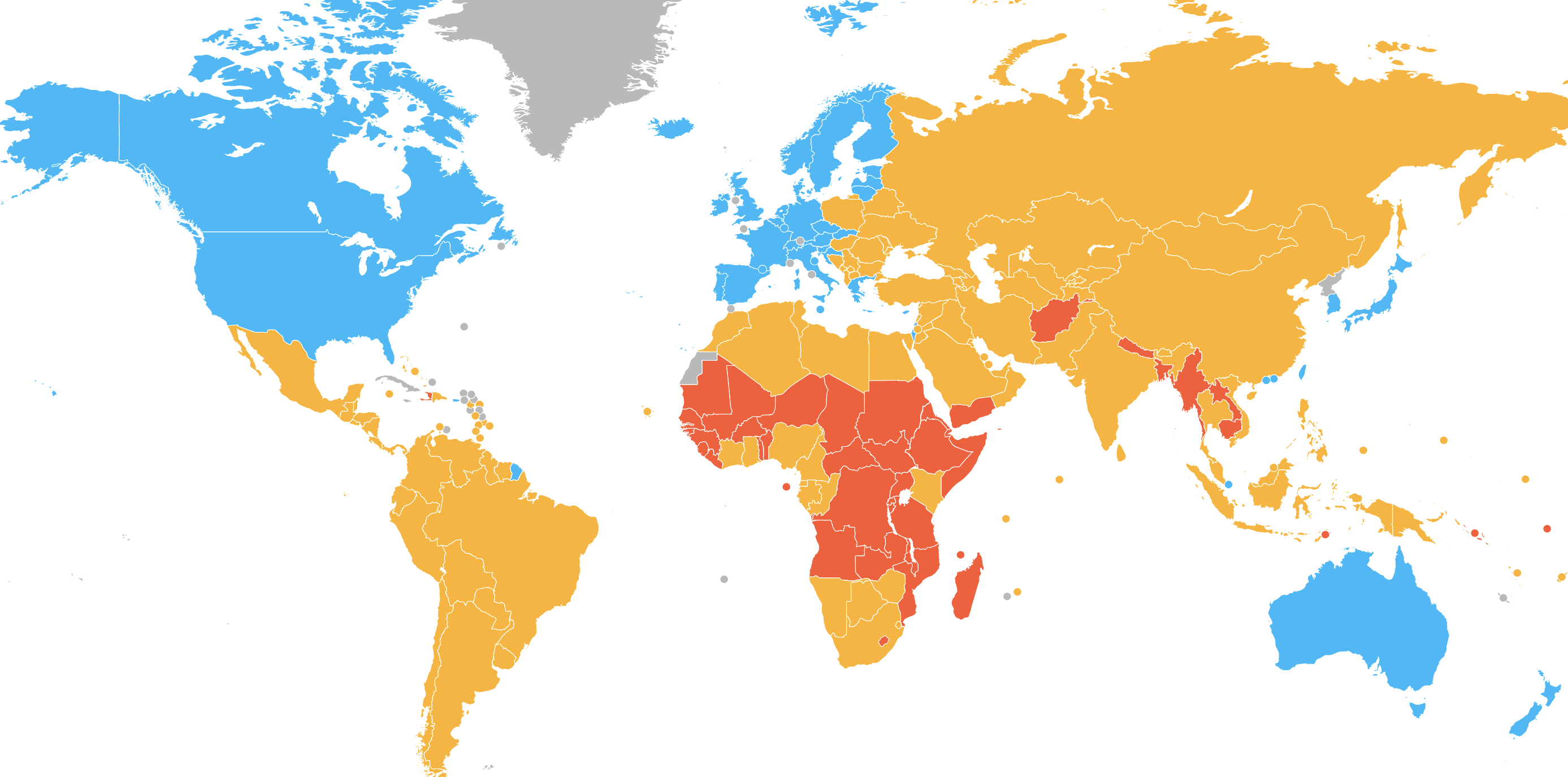

High versus Low Income Countries

The World Bank offers another widely used framework for categorizing nations, based on a single economic indicator: Gross National Income (GNI) per capita. Using this metric, the Bank classifies all economies into four main groups: low-income, lower-middle-income, upper-middle-income, and high-income. These categories are determined by specific income thresholds, which the Bank adjusts annually to account for factors like international inflation. Unlike the UN’s multidimensional LDC criteria, which include human assets and economic vulnerability, the World Bank’s approach is strictly economic, providing a clear but narrow snapshot of national prosperity based on average income.

In blue are high-income economies, according to the World Bank

This GNI-based classification is highly influential, providing a straightforward, quantitative measure for comparing economic performance and is often used to determine eligibility for loans and development assistance. However, its reliance on a national average can mask significant internal disparities in wealth and development. A country can achieve upper-middle or even high-income status while still grappling with widespread poverty, institutional weaknesses, or poor social outcomes. The framework gives rise to important development concepts like the “middle-income trap,” which describes the difficulty many economies face in transitioning from resource-driven growth to the innovation-based model required to join the high-income bracket. It thus serves as a useful but simplified economic lens that complements the broader geopolitical and human-centered approaches to development.

China

Further complicating this global picture is the emergence of China as a new superpower, now the largest economy in the world when measured in GDP (purchasing power parity) terms. Once firmly classified as a developing country, China has undergone a dramatic transformation since the late 1900s, achieving sustained double-digit growth rates for decades and lifting hundreds of millions out of poverty. Its rapid industrialization, infrastructure expansion, and integration into global trade have redefined economic relationships both within the Global South and between the South and North.

Yet China’s classification remains contested: while it rivals advanced economies in industrial output and technological capability, significant regional inequalities and pockets of poverty persist. Therefore, in development analysis, China occupies a unique position, simultaneously a member of the Global South in political forums and a peer competitor to the most advanced economies.

Non-Economic Approaches to Development

While income and industrial capacity are central to economic development metrics, they do not capture the full picture of human well-being. The United Nations Development Programme’s (UNDP) Human Development Index (HDI) is one of the most widely used alternative measures, incorporating life expectancy, education, and per capita income into a composite score. This multidimensional approach allows for a more nuanced assessment of progress, highlighting cases where countries may achieve high human development despite modest GDP levels, or conversely, where wealth coexists with poor health or education outcomes.

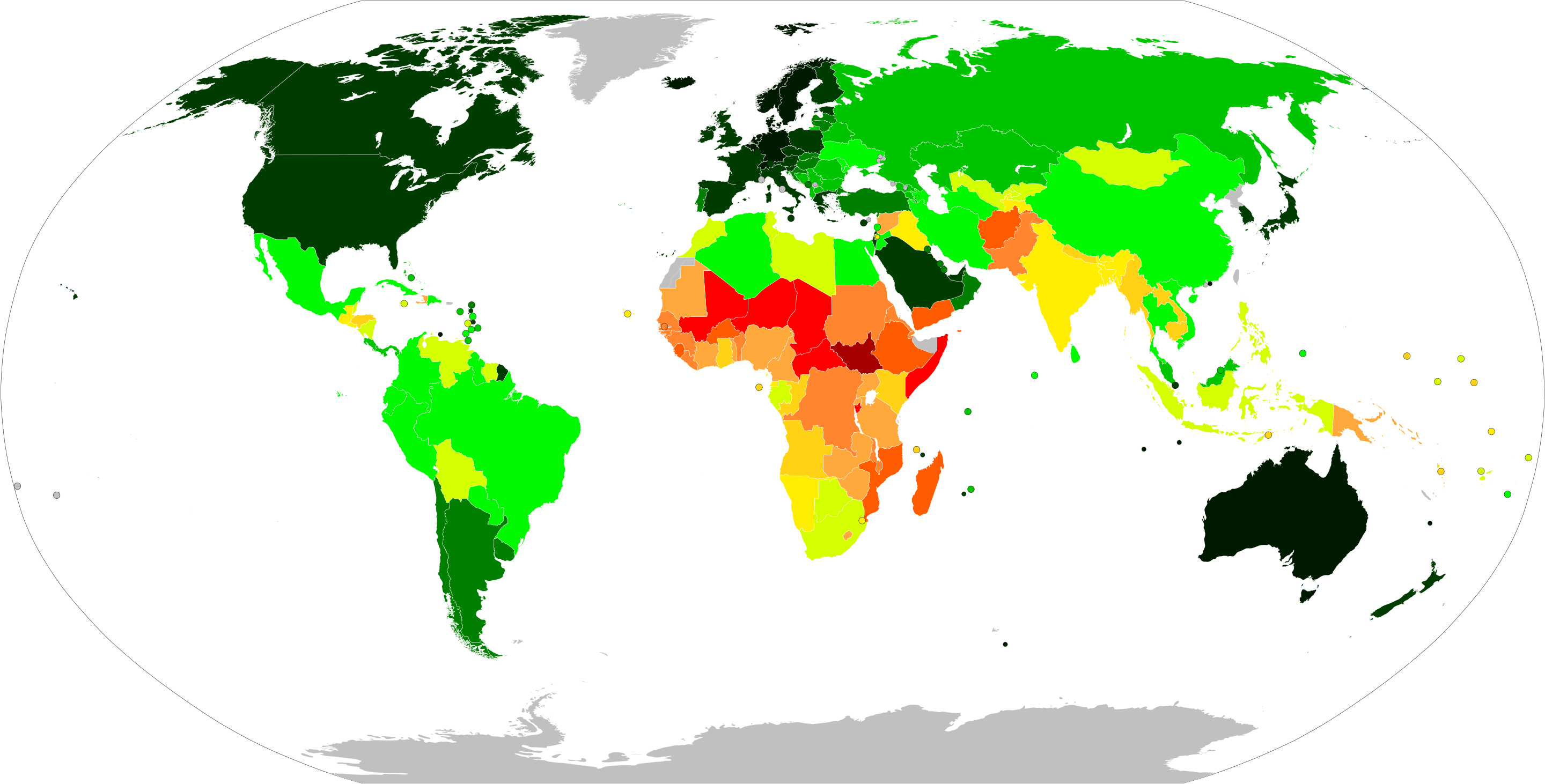

Human Development, according to the UNDP

By integrating social indicators, the HDI underscores that development involves more than economic output; it also entails improvements in quality of life, social equity, and opportunities for human flourishing. In this way, it complements and sometimes challenges purely economic classifications like developing or emerging, revealing the complexities behind global development patterns.

Conclusion

In sum, the language used to describe global development is a collection of analytical tools rather than a reflection of fixed, uniform realities. Frameworks like the Global North-South divide, and categories such as Least Developed Country or Emerging Market, provide essential structure for understanding global inequality and economic change. However, these labels often obscure the vast diversity within regions and can fail to capture the nuances of a rapidly evolving world. The unique trajectory of nations like China and the broader perspective offered by non-economic metrics like the HDI demonstrate the limitations of any single classification. Ultimately, a critical awareness of these concepts--that is, of their utility, their history, and their shortcomings--is fundamental for a nuanced analysis of the challenges and opportunities facing the developing world.

Video

A look Inside how China became the world leader in electric vehicles [6m 25s]

This video by the BBC explores China's dominant and rapidly growing electric vehicle (EV) industry. It highlights how heavy government subsidies have fueled a boom, turning the nation into the world's leader in EV production and adoption. The video concludes by noting the global implications of China's rise, as Western nations impose tariffs on Chinese EVs while acknowledging their potential role in meeting climate targets.

Discussion

1. The Utility of Labels: The text describes terms like “developing world” as “convenient shorthands.” In what ways are these labels useful for analysis? Conversely, what are the primary dangers or inaccuracies of relying on such broad classifications?

2. Challenging Categories: Using the text's example of China, explain how a single nation's unique trajectory can challenge and complicate traditional development frameworks like the Global North-South divide.

3. Economics vs. Well-being: How does the Human Development Index (HDI) provide a more holistic view of a country's progress than economic metrics like GDP alone? Discuss a hypothetical scenario where a country could have a high GDP but a low HDI. What might be happening in that country?

4. Roots of Disparity: The text links the North-South divide to "historical patterns of colonialism, resource extraction, and structural inequality." Discuss how these historical factors could create long-lasting economic disadvantages for certain regions of the world.

Critical Thinking

1. Consider a country that has transitioned from a developing to a developed economy. To what extent would its cultural or historical identity still be rooted in the Global South?

2. The section on China notes its unique position as both a Global South member in political forums and a competitor to advanced economies. How does this dual status challenge the utility of the Global North-South classification?

Further Investigation

1. The text mentions the middle-income trap. Choose an emerging market and research its economic history to determine if it is currently facing this challenge. What specific economic, political, or social factors seem to be hindering its transition to a high-income economy?

Notes: Country data were sourced from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the CIA World Factbook; maps are from Wikimedia, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike (BY-SA). Rights for embedded media belong to their respective owners. The text was adapted from lecture notes and reviewed for clarity using Claude.

Last updated: Fall 2025