The global tea industry (India; Sri Lanka)

As the world's second-most consumed beverage after water, tea functions as both a significant component of the global economy and a product of deep cultural importance. With a market valuation exceeding $150 billion in 2025, the industry provides livelihoods for millions, particularly in developing countries. The sector is currently defined by evolving consumer preferences, significant ethical challenges in its labour practices, and increasing environmental pressures.

Global Production

Global tea production is concentrated in a few key nations. China is the largest producer, cultivating a wide spectrum of teas including green, oolong, and pu-erh. India is the second-largest, known for its Assam and Darjeeling varieties. Kenya is the world's leading exporter of black tea, with the crop forming a critical part of its national economy. Other major producers such as Sri Lanka, Vietnam, and Turkey contribute distinct tea varieties to the global market. Although black tea maintains the largest market share, other categories are experiencing faster growth, indicating a significant shift in global consumption patterns.

Tea plantations in Sri Lanka, as imagined by chatGPT v5.

Shifting Consumer Preferences

Consumer behaviour is trending toward products perceived as healthier, more ethically sourced, and of higher quality. This shift manifests in several key areas:

- Health and Wellness Teas: There is increased demand for teas marketed with specific health benefits. Blends incorporating ingredients like turmeric, chamomile, and ginger are growing in market share, driven by consumers who use tea as part of a health-conscious lifestyle.

- The Rise of Specialty and Premium Teas: A segment of the market is developing a preference for single-origin, artisanal, and rare teas. These consumers are willing to pay higher prices for distinct flavor profiles and verifiable product origins.

- Demand for Sustainability and Ethical Sourcing: Consumers are showing a growing preference for transparency in supply chains. Certifications from organizations like Fairtrade and the Rainforest Alliance, which audit environmental and labour practices, are becoming more significant factors in purchasing decisions.

- Convenience-Oriented Products: The demand for convenience has driven growth in the ready-to-drink (RTD) and cold brew tea markets, which make higher-quality tea more accessible.

Labour and Environmental Challenges

The tea industry faces significant, systemic challenges related to its labour practices and environmental sustainability.

- Labour Conditions: In many production regions, labour conditions are a primary area of concern. The workforce, predominantly female, often contends with low wages, long hours, and inadequate access to housing and healthcare. Reports of debt bondage and the suppression of labour rights are also present in parts of the sector, creating cycles of poverty.

- Climate Change Impacts: As a climate-sensitive crop, tea is highly vulnerable to environmental shifts. Changes in rainfall patterns, extended droughts, and rising temperatures are reducing the geographic areas suitable for cultivation in key countries like Kenya and Sri Lanka. These factors impact not only yield but also the chemical composition of the tea leaf, which determines its quality and flavor.

Technological and Structural Responses

The industry is beginning to adopt technological and structural changes in response to these challenges. Technological advancements are being implemented in both cultivation and processing. Precision agriculture, using AI-powered sensors and drones, is used to monitor crop health and optimize resource use. In processing, AI is being applied to standardize quality control, and automated harvesting is under development to address labour issues. Furthermore, digital platforms are creating more direct-to-consumer sales channels, which can increase supply chain transparency.

The long-term sustainability of the industry will depend on its ability to integrate these innovations while addressing its fundamental labour and environmental issues through structural reforms.

Tea Workers in India

The global reverence for Indian tea stands in stark contrast to the profound and persistent hardship faced by the millions of labourers who cultivate it. The challenges facing tea workers in 2025 are not new; they are the modern expression of a system built during the colonial era, designed to extract maximum value from both the land and its people. This legacy continues to define the lives of workers in India's primary tea-growing regions.

In Assam, which produces over half of India's tea, the plantation system often operates as a total institution. Workers, many of whom are descendants of the tribal communities brought here as indentured labourers in the 1800s, live in plantation-provided housing, rely on plantation-run health services, and receive subsidized food rations. While these provisions are mandated by law, they are used to justify cash wages that fall well below the state's minimum wage for other agricultural workers. This dependency traps families in a cycle of poverty, where their home, healthcare, and livelihood are entirely controlled by their employer.

In Darjeeling, home to the world's most expensive and celebrated teas, the paradox is even sharper. The skilled, predominantly female workforce plucks the premium Darjeeling tea that fetches enormous prices on the international market, yet they see almost none of this value returned in their wages. The work is seasonal and precarious. Furthermore, many plantations have been abandoned by owners, leaving thousands of families without work, housing, or basic services, forcing them into a struggle for survival in the isolated Himalayan foothills.

In the southern states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu, particularly in the Nilgiri hills, the situation is different but still challenging. While state-wide social development and literacy are higher, tea workers still contend with low wages and the increasing casualization of labour, which strips them of the few social security benefits full-time employment once offered. Here, many work on smaller farms rather than the vast estates of the north, but the economic pressures remain the same.

Tea Workers in Sri Lanka

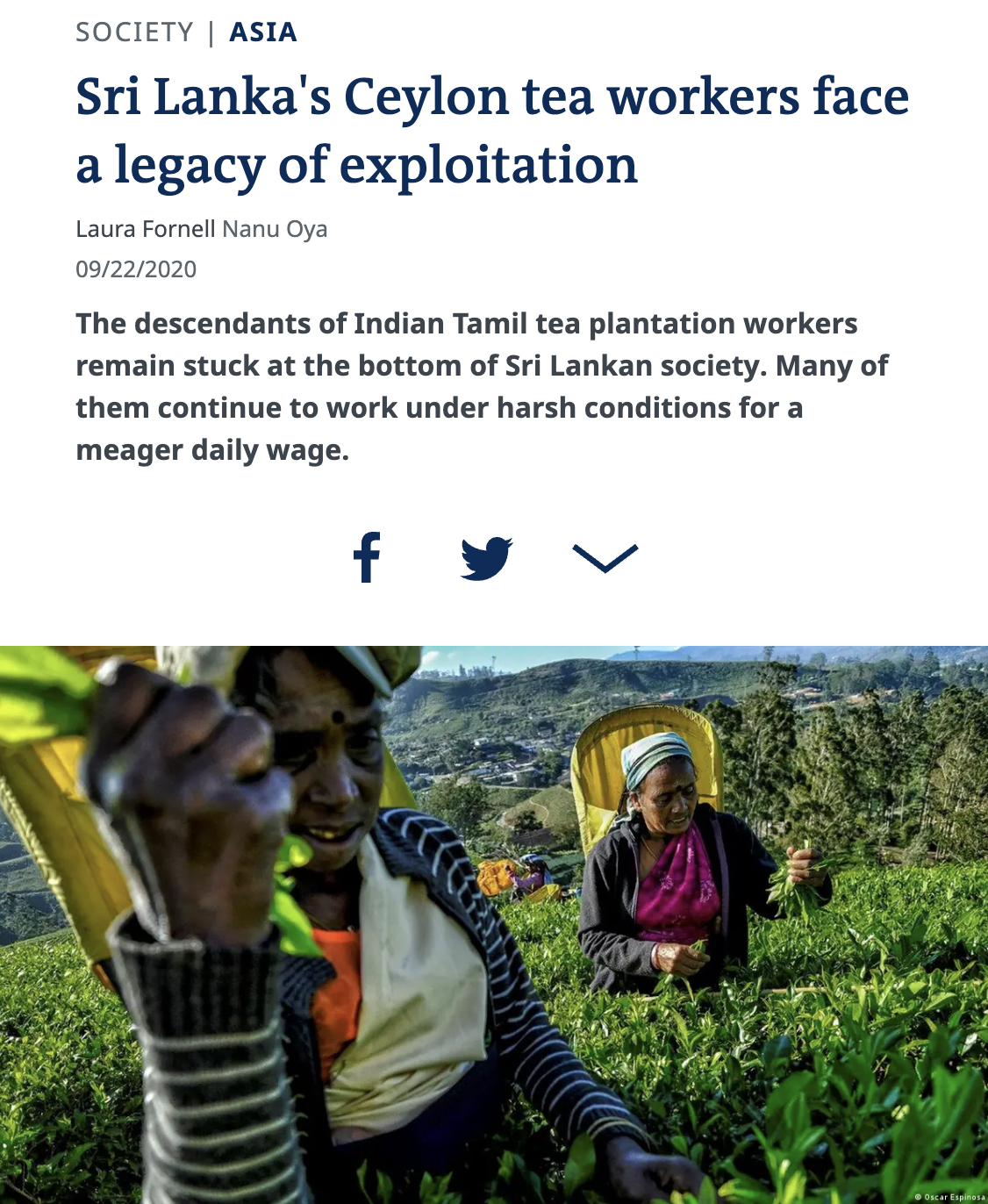

The world knows Ceylon Tea as a symbol of quality, a legacy brand born in the misty highlands of Sri Lanka. Yet, behind this celebrated beverage lies a story of profound historical injustice and ongoing struggle. The industry was a colonial creation, built by the British in the 1800s on land cleared for the purpose. Its success was made possible only by the importation of vast numbers of indentured labourers from South India, who were brought over to perform the grueling work of cultivating and harvesting the crop. Their descendants, now known as the Malaiyaha (Hill Country) Tamils, form a distinct community whose identity is inseparable from tea, and whose present-day challenges are rooted in this difficult past.

Source: Sri Lanka's Ceylon Tea Workers Face a Legacy of Exploitation

The most defining event for the Hill Country Tamils occurred after Sri Lanka gained independence in 1948. In a move to define the new nation's citizenry, the government passed laws that effectively stripped this entire community of its citizenship. Overnight, nearly a million people were rendered stateless, belonging neither to the country of their birth, Sri Lanka, nor their ancestral homeland, India.

This act of political exclusion had devastating and lasting consequences. For decades, the Malaiyaha Tamils were denied the right to vote, own land, or access the same state education and healthcare systems available to other Sri Lankans. Trapped on the plantations, their lives were entirely governed by estate management. Although citizenship was finally restored after a protracted, decades-long political struggle that concluded with a landmark act in 2003, the deep socio-economic damage of that period persists. The community entered the modern era from a position of profound disadvantage, a legacy that continues to limit their opportunities.

Contemporary Realities in Sri Lanka

Today, the living conditions for many tea workers remain a direct inheritance from the colonial era. Most families still reside in "line rooms," which are cramped, barrack-style, long buildings, with individual family units arranged side-by-side in a straight line with minimal sanitation and privacy. These housing conditions that have seen little improvement in over a century.

While the tea industry is a cornerstone of the Sri Lankan economy, generating over a billion dollars in annual exports, the wages paid to its workers remain critically low. The workforce is predominantly female; women perform the physically demanding labour of plucking tea leaves for long hours, yet their earnings are often insufficient to lift their families out of poverty. This economic pressure has led many men to seek better-paying, often temporary, work off the estates, disrupting family and community structures.

Economically, Sri Lanka's reliance on traditional, labour-intensive harvesting methods makes it vulnerable. While this manual process is essential for producing the high-quality orthodox teas for which it is famous, it faces stiff competition from more mechanized producers in other countries. In a global market that constantly pressures producers to lower costs, the wages and welfare of Sri Lanka's tea workers are the first to be squeezed.

Sri Lanka: Key Facts

- Capitals: Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte, Colombo

- Largest city: Colombo (~753,000 people)

- Population: 21.8 million (2024)

- Official languages: Sinhala, Tamil

- GDP (ppp): 342.6 billion (IMF 2024)

- GDP rank (ppp): 62

- GDP per capita (ppp): 15,632 USD

- GDP per capita rank: 109

- Exports to: USA 22%, India 7%, Germany 7%, UK 7%, Italy 5% (2023)

- Imports from: India 21%, China 19%, UAE 10%, Singapore 5%, Malaysia 4% (2023)

Video

The Global Tea Industry [6m 09s]

The video explains how tea, first cultivated in China, was transformed into a global commodity by colonial powers like the British, who established large-scale plantations in India and Sri Lanka. It details the journey of tea from harvesting and processing on farms to being sold at auction, and then distributed globally through a network of exporters and importers.

Discussion

1. In what specific, tangible ways do the descriptions of the plantation systems in Assam and the "line rooms" in Sri Lanka support the claim that modern labour challenges are a modern expression of a system built during the colonial era?

2. A consumer in Europe buys a box of Fairtrade certified Assam tea. To what extent are they solving the problems described in the text (low wages, dependency), and to what extent are they simply alleviating their own conscience without prompting structural change?

3. The Assam plantation system is described as a total institution. Using the information provided (housing, rations, healthcare), discuss the extent to which this system creates a cycle of dependency that is arguably more powerful than low wages alone.

4. In both India and Sri Lanka, the workforce is noted as being predominantly female, with Sri Lankan men often seeking work elsewhere. Discuss the potential long-term impacts of this gendered labour structure on family dynamics, community stability, and women's empowerment?

5. How does the consumer trend toward health and wellness teas (e.g., with turmeric) in Western markets connect to the economic reality of a worker in the Nilgiri hills of South India, where such ingredients might be grown? Is the connection positive, negative, or neutral?

Critical Thinking

1. Effectiveness of Market-Based Solutions: The text suggests that consumer demand for ethical sourcing and certification systems can drive meaningful change in labour conditions. Critically evaluate this causal inference by examining what evidence would be needed to support this claim. Consider whether correlation between increased ethical certifications and improved conditions necessarily implies causation, or whether other factors might explain any observed changes. Analyze the assumptions underlying market-based approaches to social problems and evaluate alternative explanations for why labour conditions persist despite growing consumer awareness and certification programs.

2. Historical Causation and Contemporary Responsibility: While the text attributes current labour conditions to colonial-era systems, examine whether this historical framing adequately explains the persistence of these conditions in the present day. Consider what other factors (e.g., economic, political, technological, or social) might contribute to maintaining current structures. Evaluate whether the text's emphasis on historical origins might oversimplify the complex web of contemporary decisions and incentives that shape industry practices. Assess what evidence would help distinguish between conditions that are genuinely constrained by historical legacies versus those maintained by current choices and interests.

Further Investigation

1. Comparing across Production Systems: Research different organizational models in tea production worldwide, including large plantations, smallholder farms, cooperatives, and vertically integrated operations. Analyze the economic outcomes, labour conditions, and environmental impacts associated with each model, examining both benefits and drawbacks. Investigate how different regulatory environments, market structures, and cultural contexts influence the viability of various approaches. Compare productivity metrics, worker compensation, quality outcomes, and sustainability measures across these different systems to develop a nuanced understanding of their relative strengths and limitations.

2. Policy Impact Assessment: Examine how different government policies, ranging from labour regulations to trade agreements to agricultural subsidies, have influenced conditions in tea-producing regions. Research specific policy interventions and their measurable outcomes, including both intended and unintended consequences. Investigate the role of international organizations, certification bodies, and trade agreements in shaping industry practices. Analyze how different institutional frameworks have succeeded or failed in addressing various challenges, and consider what factors contribute to effective policy implementation in this sector.

Notes: Country data were sourced from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the CIA World Factbook; maps are from Wikimedia, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike (BY-SA). Rights for embedded media belong to their respective owners. The text was adapted from lecture notes and reviewed for clarity using Claude.

Last updated: Fall 2025