Turkish Guestworkers in Germany

Introduction: Why this case matters

The experience of Turkish guestworkers is a pivotal case in the history of labour migration. Now spanning over six decades, the case has drawn sustained attention across disciplines because it brings together a wide range of interconnected issues: migration, citizenship, identity, belonging, racism, cultural integration, Islam-West relations, and the long-term consequences for public policy. As such, it offers a lens through which to examine not only labour markets, but also broader questions of social change, cultural encounter, and political response.

Germany: Key Facts

- Capital: Berlin

- Largest city: Berlin (4.7 million)

- Population: 84 million (2025)

- Official language: German

- GDP (ppp): 6.1 trillion (IMF 2025)

- GDP rank (ppp): 6

- GDP per capita (ppp): 72,599 USD

- GDP per capita rank: 19

- Export partners: USA 10%, France 8%, Netherlands 7%, China 7%, Italy 6% (2023)

- Import partners: China 12%, Netherlands 7%, USA 7%, Poland 6%, France 5% (2023)

Turks in Germany Today

• Over 4 million people of Turkish origin live in Germany, making up roughly 5% of the population.

• The majority of Turks in Germany are now German citizens.

• More than 80,000 businesses in Germany are owned by people of Turkish origin, employing an estimated 400,000 workers. At the same time, a Turkish minority underclass also persists.

• Many still visit Turkey every summer, often creating heavy traffic at border crossings.

• Turkish cafes and eateries can be found in most German cities and towns.

• Turkish neighborhoods exist throughout Germany, some resembling "mini-Turkey," such as Berlin’s Kreuzberg.

Case Background

In the years following the Second World War, many economies in Western and Northern Europe faced severe labour shortages. Domestic workforces were insufficient to meet the demands of rapidly expanding industries. Germany was among the countries most affected, and to address the gap, it signed bilateral agreements with several nations to recruit foreign workers.

In October 1961, Germany and Turkey concluded a formal recruitment agreement, marking the official beginning of the Turkish guestworker program in Germany. Between 1961 and 1973, roughly 2.7 million Turks applied for these jobs, with more than 700,000 ultimately securing employment.

Although originally conceived as a temporary measure, the guestworker program had long-term consequences that were unforeseen. The following sections examine how Germany’s initial expectations diverged from the program’s enduring social and demographic impact.

1961

In 1961, a wave of Turkish workers embarked on a journey that would profoundly change their lives. Turkey was struggling with high unemployment, and for many, the chance to work in Germany promised a way out of economic hardship. Most were young or middle-aged men, though women also joined the migration in meaningful numbers. Some were single, venturing abroad alone; others left behind spouses and children who depended on the money they would send home. For many, this separation was emotionally difficult, as they faced the uncertainty of sending money back while missing family milestones and everyday life at home.

In 1961, a wave of Turkish workers embarked on a journey that would profoundly change their lives. Turkey was struggling with high unemployment, and for many, the chance to work in Germany promised a way out of economic hardship. Most were young or middle-aged men, though women also joined the migration in meaningful numbers. Some were single, venturing abroad alone; others left behind spouses and children who depended on the money they would send home. For many, this separation was emotionally difficult, as they faced the uncertainty of sending money back while missing family milestones and everyday life at home.

Education levels were generally low, and very few spoke German. Many came from small towns or rural areas, often encountering urban life for the first time when they arrived in Germany. For some, stepping off the train into cities like Hamburg or Munich was their first experience not only in a foreign country but in a large, bustling metropolis. The sheer scale and pace of city life, combined with the language barrier, presented a steep learning curve as they adapted to unfamiliar surroundings.

The process of going abroad was demanding. The German government had set up liaison offices in Turkey to screen applicants, conducting interviews and medical examinations that could be intrusive or even humiliating. Those who passed boarded trains to Germany with the expectation of returning home after a year or two. Many carried a mix of hope and apprehension, uncertain whether they would adapt to a completely new culture and way of life. In practice, however, the temporary stay often stretched into many years.

Initially, the German authorities referred to these workers as “foreign workers,” a term weighed down by the dark history of forced labour during the Second World War, when millions of foreign civilians and prisoners of war had been exploited under the same label. To avoid these associations, the term “guestworkers” (Gastarbeiter) was later adopted, framing the migration as temporary and mutually beneficial, even as it laid the foundation for a long-lasting Turkish presence in Germany.

The Initial Guestworker Experience (1961-1973)

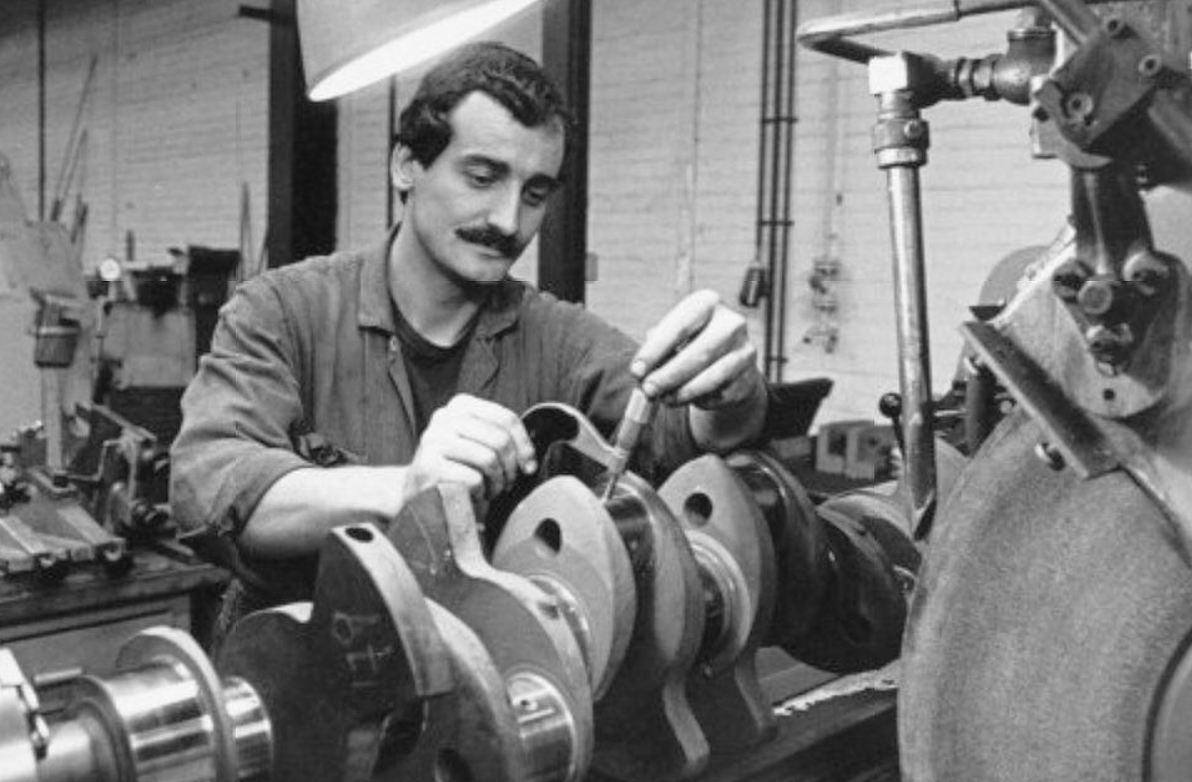

Upon arrival, Turkish guestworkers received brief training before being assigned primarily to heavy industry, factories, or mining. While some had been promised factory jobs, many found themselves spending years performing grueling work deep underground in mines, particularly in industrial cities such as Essen. The labour was physically demanding and often harsh, yet both men and women persevered for years.

Turkish guestworkers in Germany in the 1960s, as imagined by chatGPT v5.

Guestworkers typically lived in dormitories (Heim) near their workplaces, which were often overcrowded and lacked basic amenities such as bathrooms. These accommodations were isolated from the surrounding German communities, reinforcing social segregation and contributing to a sense of alienation.

At first, the guestworkers intended to endure these hardships only temporarily, aiming to save as much as possible before returning to Turkey. Although their wages were comparable to those of German workers, the money had much greater purchasing power back home. As a result, many lived frugally, prioritizing remittances over spending in Germany. Their work permits were generally valid for one or two years, after which they expected to be replaced by new recruits.

Over time, however, this system began to change. Employers recognized that continually hiring and training new workers was costly, inefficient, and time-consuming, particularly when experienced workers were already on the job. In response, the 1964 recruitment agreement was revised to remove time restrictions, effectively ending the practice of rotating guestworkers.

Working in Germany, Thinking about Turkey

The period between 1961 and 1973 was emotionally taxing for Turkish guestworkers. Though physically present in Germany, many remained deeply connected to Turkey in their hearts and minds. The question of returning home was often one of timing rather than possibility, creating a persistent inner conflict.

Decisions about whether to stay or return were frequently agonizing. Life in Germany was demanding, marked by grueling work, social isolation, and language barriers. Workers often yearned for their families, hometowns, and familiar routines in Turkey. At the same time, their stable incomes provided essential support to relatives back home. These conflicting pressures left many in a continual state of emotional tension.

Munich’s main train station in southeastern Germany was the first point of arrival for many guestworkers, and it soon became a symbolic threshold between their lives in Germany and their distant homes in Turkey. In an era without the internet or smartphones, workers would sit or stand for hours, smoking and gazing at the tracks, quietly dreaming of home, or their next trip, if not return. To German onlookers, including the police, their lingering seemed mysterious until the Turkish embassy explained that these contemplative pauses were expressions of profound homesickness.

Communication with family in Turkey was slow and challenging. Letters, postcards, and voice messages recorded on cassette tapes were common methods of contact. Telephone calls were limited by operator-dependent landlines, and digital communication did not exist.

The Oil Crisis of 1973

Germany experienced a brief economic recession between 1966 and 1967, during which some workers lost their jobs. In response, politicians, scholars, and commentators began criticizing foreign labour recruitment programs, and xenophobic sentiments toward migrant workers started to emerge. Despite this growing tension, no major incidents occurred until 1973.

The recruitment system functioned relatively smoothly until the oil crisis of 1973, which severely affected Germany and other Western nations. By that time, Germany was home to four million non-citizens, many of whom lost their jobs due to the economic downturn. German authorities anticipated that guestworkers would return to their home countries, but most did not leave immediately. Many Turkish guestworkers, in particular, had spent over a decade in Germany, establishing families and communities. Although they often considered returning to Turkey, a recent job loss rarely prompted an immediate departure.

This unexpected reluctance surprised German policymakers, prompting the government to suspend new migrant worker recruitment and tighten immigration policies. However, a key provision in the 1964 revision of the recruitment agreement had lifted time restrictions and ended mandatory worker rotation, making deportations impossible. What initially seemed a minor administrative change ultimately had far-reaching consequences in 1973, shaping the social fabric of Germany for decades to come.

Family Reunifications

Workers faced significant risks if they chose to leave Germany and later attempted to return legally. For this reason, many decided to remain, bringing their families to join them out of concern over potential future immigration restrictions. Even those who considered eventually returning to their home countries preferred to keep their families close, preparing for unforeseen circumstances that could prolong their stay in Germany.

Family reunifications became increasingly common throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Although the German government initially opposed allowing guestworkers to bring their families, it lacked the legal authority to prevent it. Family reunification is recognized as a fundamental human right under several international agreements. Both the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights underscore the state’s duty to protect family integrity. In addition, a specific UN convention safeguards the rights of migrant workers and their families.

Consequently, Germany could neither expel guestworkers nor prevent them from working or reuniting with their families. This legal reality produced an unexpected development: migrant workers gained the right to remain, seek new employment, and sponsor the arrival of their spouses and children. Over the following two decades, women and children arrived steadily, transforming the social landscape.

Long-separated families were reunited, and single guestworkers, anticipating possible future restrictions, married and sponsored their wives. Most of these new arrivals had never lived in Germany and spoke little or no German. Their presence profoundly altered the environment of the guestworkers, converting previously isolated male dormitories into vibrant, growing communities.

Key Transition in the 1980s: From Workers to Communities

As more guestworkers married and had children, Turkish neighborhoods began to emerge across the country, gradually reflecting aspects of life in Turkey. Religious practices initially took place in makeshift spaces, such as converted warehouses. However, as these communities grew and became more established, Turkish residents began seeking permission to construct purpose-built mosques, complete with domes and minarets reminiscent of those in their homeland.

Local authorities were initially hesitant, arguing that such structures did not align with Germany’s social or architectural norms. Despite this resistance, purpose-built mosques gradually appeared in Turkish neighborhoods throughout the country, symbolizing the growing permanence and visibility of these communities.

Return?

An estimated half of the 700,000 guestworkers who arrived in Germany eventually returned to Turkey, a process that occurred in several waves. The first wave of returnees took place during the 1966-1967 recession. These workers had spent only a few years in Germany and returned after losing their jobs. The second wave occurred following the 1973 oil crisis, when Germany halted new recruitment. Many who were unable to secure new employment returned to Turkey. A third and more significant wave occurred in the mid-1980s. The German government, under Chancellor Helmut Kohl and Interior Minister Friedrich Zimmermann, offered a cash incentive for guestworkers to return. This program provided 10,500 German marks per adult and an additional 1,500 marks per child. This led to a notable surge, with 250,000 Turks returning by mid-1984. These returnees had often spent up to two decades in Germany, saved money, and many chose to return to ensure their children were raised with a strong Turkish or Kurdish identity.

Later returnees in the 1990s and beyond were different. Many had lived in Germany for over 30 years and were more fluent in German and socially integrated than earlier returnees. They often returned after retirement, becoming semi-returnees who spent part of the year in Turkey while maintaining residency in Germany to access social security benefits. Their children typically remained in Germany.

1989 and Beyond

This story has many phases, each marked by countless individual migrant experiences. One of the darker chapters began in 1989 with the fall of the Berlin Wall and German reunification. As workers from East Germany moved west, racist violence increased. Nazi ideology had persisted in certain areas of the former East Germany, and neo-Nazi activity became more visible. Attacks on immigrants escalated in the years following reunification.

One of the most severe incidents occurred in 1993, when five members of a Turkish family were killed in an arson attack in Solingen. The case drew widespread attention and remains a central reference point in discussions of anti-immigrant violence in Germany, though similar attacks had occurred earlier in Duisburg-Wanheimerort (1984) and Mölln (1992).

Between 2000 and 2006, a neo-Nazi terrorist group known as the National Socialist Underground (NSU) carried out a series of murders, targeting people of Turkish, Kurdish, and Greek descent. For years, authorities failed to recognize either the pattern of attacks or their political motivations. The full scope of the group’s activities was only publicly acknowledged in 2011.

In February 2020, a far-right gunman carried out a mass shooting in Hanau, attacking two shisha bars and nearby locations. Nine people were killed, most of whom were immigrants or of immigrant background, including individuals of Turkish, Kurdish, Bosnian, Afghan, and Bulgarian descent. After the attack, the perpetrator killed his mother and then himself. He had previously published a manifesto containing racist conspiracy theories targeting immigrants and ethnic minorities. The Hanau attack highlighted ongoing failures in identifying and monitoring far-right extremism and raised urgent questions about how state institutions protect migrant communities from such threats.

Emerging Realities

Second and Third Generation Descendants with Hybrid Identities: The children and grandchildren of Turkish guestworkers have developed complex identities that blend German and Turkish elements. Unlike their grandparents who dreamed of returning to Turkey, these generations consider Germany home while maintaining cultural connections through family, food, and traditions. Many speak German as their native language but navigate between competing cultural expectations, creating unique hybrid identities that reflect their position between two worlds.

Hybrid Urban Landscapes: German cities now feature distinctly hybrid neighborhoods where Turkish bakeries sit alongside German businesses, Ottoman-style mosques rise near apartment blocks, and markets sell both traditional Turkish produce and German goods. Areas like Berlin's Kreuzberg have become tourist destinations showcasing this cultural fusion, while contributing significantly to local economies through over 80,000 Turkish-owned businesses that employ hundreds of thousands of workers.

German Rap as Voice for the Underclass Migrants: Turkish-German youth have embraced rap music to express experiences of marginalization, identity confusion, and economic struggle. Artists integrate words from Turkish, Kurdish and other languages into primarily German rap lyrics, articulating the challenges of being perceived as foreign despite German citizenship. For Turkish youth who didn't identify with Germany as a homeland, localized German hip hop initially did not appeal to them, leading Turkish artists to use German hip hop as a springboard for their own expression. This musical movement gives voice to the persistent Turkish underclass, serving as both social commentary and cultural bridge while creating new pathways for expression and economic mobility.

Video

A look into the lives of three generations of Turkish immigrants in Germany [8m 42s]

The video delves into the stories of three generations of Turkish immigrants in Germany, starting with the first generation who came as "guest workers" in the 1960s. It explores their initial reasons for coming, their intentions to return to Turkey, and how their plans changed as they established roots and raised families in Germany. The narrative then shifts to the second and third generations, who share their perspectives on what "home" means to them, their experiences with acceptance and discrimination in Germany, and how they navigate their dual cultural identity.

Bonus content 1: The music video Der Gastarbeiter (The Guestworker) by Turkish-German rapper Eko Fresh tells the story of his grandfather’s migration from Turkey to Germany. The song is in German, but YouTube’s auto-translate can help you follow along and get a sense of this personal migrant story: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yQZTntUx3Yk

Bonus content 2: A look into the Turkish community of Berlin, particularly in the Kreuzberg district, often called "Little Istanbul" due to its vibrant Turkish community: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kz6N4EYkwyU

Discussion

1. The transformation of the guestworker program from temporary labour recruitment to permanent settlement reveals how initial policy intentions can diverge dramatically from long-term outcomes. Consider how the 1964 revision removing time restrictions seemed minor at the time but proved pivotal in 1973. What does this suggest about the relationship between short-term administrative decisions and their generational consequences? How might policymakers better anticipate such unintended outcomes when designing temporary programs?

2. The concept of "home" appears to shift throughout this case, from the guestworkers' initial strong connections to Turkey to their descendants' identification with Germany as home while maintaining cultural ties. Discuss how economic necessity, family obligations, and time itself reshape people's sense of belonging. What role does the physical act of mobility play in psychological attachment to place?

Critical Thinking

1. The description of second and third-generation "hybrid identities" warrants critical examination. Analyze whether this framing adequately captures the complexity of bicultural experience or whether it oversimplifies the process of identity formation across generations. Consider what assumptions about cultural authenticity and integration may underlie such categorizations.

Further Investigation

1. Research the specific UN conventions that support the right to family reunification, and how they applied to the guestworker situation.

2. Explore how other European countries with similar guestworker programs during the same period experienced different outcomes. Investigate the specific legal, social, and economic factors that might explain variations in integration patterns, return migration rates, and community formation across different national contexts.

Notes: Country data were sourced from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the CIA World Factbook; maps are from Wikimedia, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike (BY-SA). Rights for embedded media belong to their respective owners. The text was adapted from lecture notes and reviewed for clarity using Claude.

Last updated: Fall 2025